We departed Garamba National Park on the morning of the 27th after stopping at the hospital to ask the doctor about the sores on my tongue. He thought I had Candida and prescribed a mouth wash that worked almost instantly. He had also given Mark antihistamine for his heat rash and that was helping too. We got a tour of the small, 14 bed facility with one OR a small maternity ward and a pharmacy. There were 2 MDs, and a few nurses. The doctor told us there are 20 births a month in the hospital. Malaria is a big problem as he cannot get the people to use the bed nets he distributes. He gives them out and people sell them rather than use them.

We left a small donation for the hospital and drove to the airstrip. where we waited for the caravan to take us to Entebbe. It arrived at 10am. There was plenty of room for more people, so Martin joined us to Entebbe. We arrived there at 12:30 and were met by Jonathan’s driver, David, who dropped us off at Hotel No. 5 in Entebbe. It was nicer than the Protea, where we usually stay, but it did not have a view of anything, and we missed seeing Lake Victoria from our room. We both took long showers. Then Mark chilled for the rest of the day as I worked feverishly to get the Garamba post finished. The wi fi had been problematic the entire time we were in the National Park and I had not been able to do much until we were back in Entebbe. I finally made good progress and we went to dinner. Pizza and pasta were the foods we craved. Then bed.

January 28,2024

David picked us up at 8:30 and took us back to the Entebbe airport for our 11am Ethiopian Air flight to Addis Ababa, which, at 7520, is the second highest elevation airport in the world. There we were met by a facilitator, Mr. Lewl. Good thing, as I did not have a visa, despite Marks efforts before we left home. We went through some hoops at the airport and finally, at much expense, I had a visa. The next problem was our binoculars. Although we had prepaid the fee to bring both pair, the officials would not allow Mark’s binoculars into the country, as they were too powerful and the requirements had changed to dis-allow them. So, after 2 hours of hassle, we left his at the customs office and took mine. While we waited, I watched lines of people get all of their bags ransacked. What an ordeal.

Once outside the airport we met Will, our guide and owner of Journeys by Design, his assistant Ben, and a driver. They had waited patiently and drove us to the Hyatt Regency for one more first-class hotel night before heading into the bush. While hanging out in our room, I finished the Garamba post, Mark edited it and then we published it. With that project done, we joined Will in an Asian Restaurant and started learning more about the Omo River and our journey.

The lower Omo Valley of southern Ethiopia is home to some of the world’s least changed cultural groups. The area is a melting pot of cultures and communities and represents some of the greatest genetic variance on the continent. It is sometimes described as the birthplace of mankind, and it is not hard to see why.

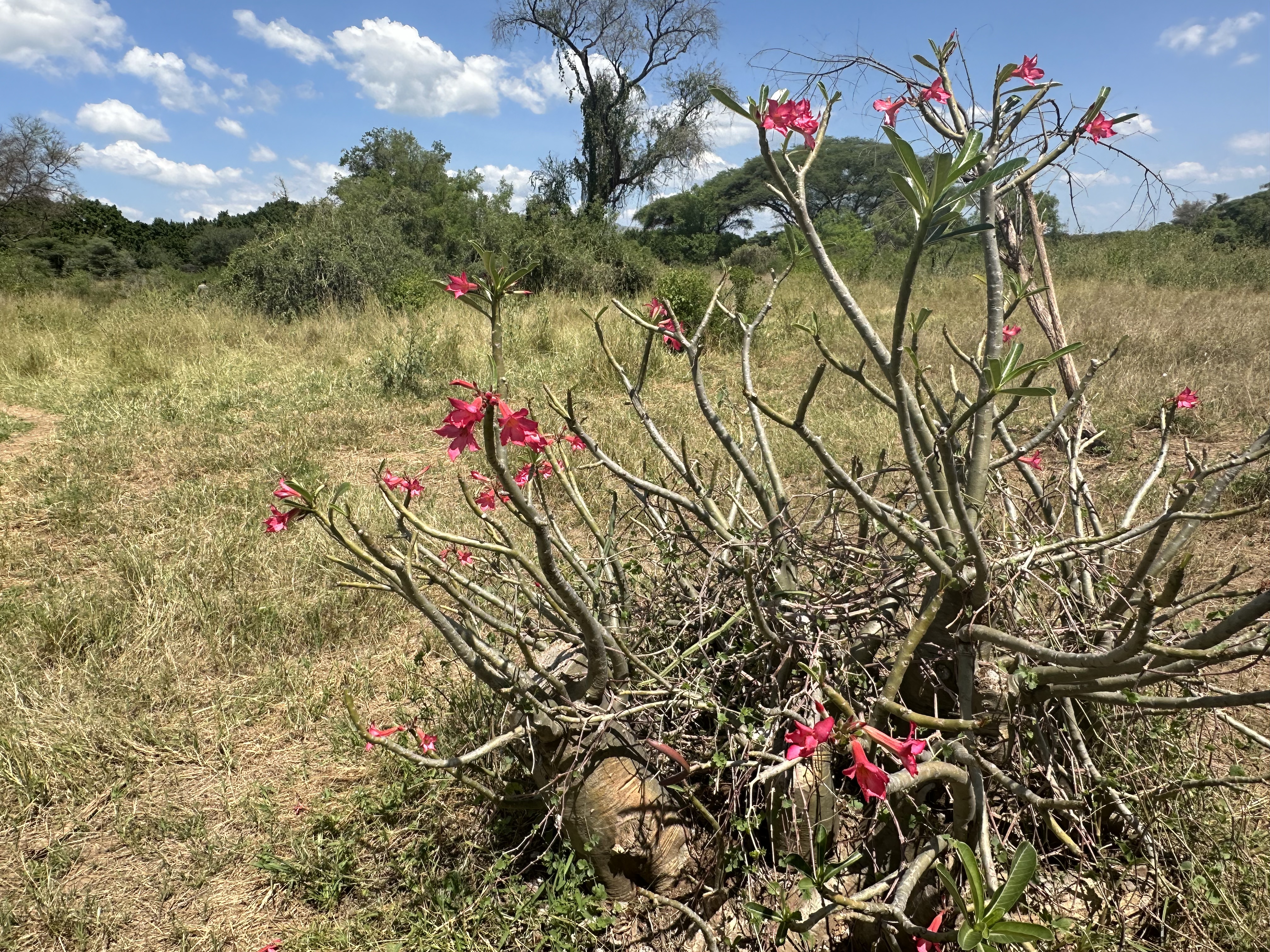

Known for their painted, pierced and scared bodies, the people of the Omo River Valley, tucked deep in the country’s southwestern corner, are some of the most unique on the African continent. Over 40 tribal groups live remotely here. Following in the footsteps of their ancestors, they are known for their cultural traditions and interaction with the physical environment—a lifestyle in harsh and unforgiving landscapes. Today for example, the temperature is above 100 degrees F. as it was yesterday and will probably be tomorrow and weeks to come. The Omo River is a lifeline for these tribes. Here are some images of our first day in the Omo Valley–a typical termite mound, goats on a typical road, white-backed vultures in a freshly planted field, sorghum growing along the banks of the Omo, a desert rose bush, our boat on the river.

The tribes rely on the river’s natural flood cycles for farming, fishing and grazing. The lower Omo Valley is very beautiful with diverse ecosystems including grasslands, volcanic outcrops and one of the few remaining pristine riverine forests in semi-arid Africa which supports a wide variety of wildlife.

The Mursi people, whom we visit first, attribute overwhelming cultural importance to cattle. They wear bones, shells and skins and practice scarification. The women are known for their clay lip plates. The lip plates are a sign of beauty and are worn only when the wife is serving food to her husband. Women start cutting their lower lip when they are about 18 and expand their lip opening over time by sticking ever larger diameter sticks in the opening. It is a very painful process. All Mursi have their lower front teeth removed when they are small children to help them survive should they get lock jaw, which they get from tetanus, a common ailment within the tribe. Notice the image of the standing woman tethered to a log. She is unhappily married to an older man and has run away a few times. Sooner or later she will have to accept her fate. The basket is so densely made that it is water tight.

January 29, 2024

Finally, we landed at Murulle, a small dirt airstrip in the lower Omo Valley at mid-day. The temperature was 98 degrees and headed for over 100. We were met by 2 men named Aewl and Gater, who both worked for Graham, the owner of our first Omo camp, called Chem Camp. We road in a Toyota SUV on very bumpy dirt roads through acacia and tamarind trees and herds of sheep and goats for about half an hour until we came to a lovely, paved road that was built by the Chinese to deliver sugar cane from the fields to Addis.

The landscape changed to fields of papaya, banana and open areas ready for planting. Anyone can rent the government owned land and plant crops. We followed that road in almost a straight line for an hour and finally reached our put in on the river. The group of people at the put in were members of a local tribe called Nyagatom. They were not friendly or welcoming, so we moved directly to the boat, where we met Graham, the camp and boat owner, and cast off. With the engine running and the wind in our faces, we were comfortable motoring upstream for the next couple of hours. Both sides of the river are covered with trees reaching down to the fast moving, light chocolate river. There were the usual birds and a few to add here: goliath heron, Egyptian plover, yellow-billed black kites and Northern Masked Weaver birds. We saw no hippo but there were several crocks along the riverbank. At last, we reached camp and moved into our tent under a large fig tree. The tent was a good size and had several screened air vents. The attached bathroom was open to the sky and had dried figs all over the floor. I pushed them out of the way, and we enjoyed the bucket shower with cool water. We were too hot to want a warm shower anyway. We slept well without bed covers most of the night.

January 30, 2024

The only cool time is in the early morning, so we were up early to enjoy it. After porridge for me and an English breakfast for Mark, Will and Graham took us for a walk through the woods to a clearing where we met the Mursi people in a small encampment. My first photo of a Mursi was of a bearded man named Chamankoro and his wife. At the encampment the men were listening to a talk about allowing tourists into their midst and why they should be agreeable. Money, medicine and education are the reasons to allow us in. After the talking, a butchered cow was thrown onto a roaring fire and shortly the crowd was happily eating the meat. I noticed there were no women present, except me. We ate a small piece and found it very tasty.

Chamankoro and his wife pose for me.

He also posed with Machetti Maron, who was the general manager of the camp. We were shown a basket made of densely woven palm fronds, such that the basket could hold water. It was very special, but too large to bring home. Nearby was a bush that had yellow hibiscus flowers that were very pretty. Some of the boys who were scared also posed for me.

I was fortunate to have several conversations with Bardoley Tula. He was the only Mursi person who is educated and speaks fluent English. He is about 26 years old and was educated by missionaries. He was adopted by a missionary family from Virginia and educated in Addis University. He has a master’s in Anthropology and in Theology. Currently, he is working for Graham as a language consultant, and “An African Canvas”, with whom he is supporting 40 Mursi students through high school. Next for us is the Chem camp crew saying posing for a good buy photo and then waving as we float away.

He told me there are 25,000 or more Mursi, despite what commercial publications say that the population is at no more than 10,000. The Mursi are not nomadic. The men have cattle farms away from the family encampment where they live on a diet of cows’ blood and milk. When in camp, they and their families subsist on sorghum, which they grow on the banks of the Omo River. They are, therefore, agro-pastoralists who they love and respect each other. They have a somewhat pagan belief system. They believe in nature and evil spirits who must be appeased. There is no life after death, but there is consideration paid to ancestors. Burials take place immediately after death, but mourning lasts for 4 days for men and 5 days for women. During the mourning period rituals take place to appease evil spirits.

Bardoley told me about a favorite game the Mursi play called Donga. It is a bit like sword fighting, but with long wooden sticks. Both parties cover themselves to keep from getting hurt and generally no one does get hurt badly. They try to bash each other until the referee declares a winner. It is supposed to be good fun. Certainly, the audience loves the game.

In recognition of Graham’s efforts to improve their circumstance, the Mursi were having a bull ceremony. At 11:30 am we walked 20 minutes through the woodland to a clearing where about 40-50 Mursi men were having a discussion about the effects of allowing tourists in their midst, while a fire roared in preparation for cooking a large bull. Someone was waxing on with questions about why should they allow tourist into their area. Then Bardoley got up and spoke about the benefits of having tourists, especially for medical assistance and schools, which are very difficult to get. The government had promised such facilities but failed to deliver. A School teacher had been unwilling to stay very long and the monthly medical clinic has not materialized. As Bardoley spoke, slabs of beef were thrown on the hot ash and cooked very quickly. When he finished, the meat was pulled out of the fire and consumed by the men using their machete’s to carve off pieces. To keep the meat clean, large bunches of green brush were used as tables to hold the uneaten meat. It smelled so good, we each had a few small pieces too. We took a lot of photos and then headed back to camp. One last image was taken of a lonesome boy at the edge of the clearing. Bardoley told us he had owned the bull and was sad about it being killed, even though he was paid for it.

As we left the camp area we saw some Mursi huts on the hill top.

In the late afternoon we motored upriver looking for birds, monkeys, and crocks for about 2 hours, then floated down stream back to camp while drinking our beers. We saw one big crock, who did not run into the river. There were colobus monkeys, and some birds like: Bataleur and Open billed storks. The Mursi had their sorghum fields on the left riverbank and the Nyagantom Tribe had their fields on the right bank. We spent very little time with the Nyagantom people as we found them very unwelcoming.

Back at camp we had cocktails, dinner, nice cold showers, and bed.